|

William

Egan Colby

May 14, 1996

The remains of former CIA Director William Colby were buried with military honors Monday at Arlington National Cemetery. After a private service for family and friends, an urn bearing Colby's ashes was transported by horse-drawn caisson to its final resting place in a clearing surrounded by maple and pine trees. Army marksmen fired a 21-gun salute, and a bugler played taps as a flag was presented to Colby's wife, Sally Shelton-Colby.

Colby, 76, disappeared April 27 while canoeing near his Rock Point, Maryland., vacation home. His body was recovered eight days later.

Autopsy finds Colby likely collapsed before falling out of canoe: May 11, 1996

BALTIMORE (AP) -- Former CIA director William Colby died from drowning and hypothermia after apparently collapsing from a heart attack or stroke and falling out of his canoe, the state's medical examiner said Friday.

Colby's body was found Monday after an eight-day search that included helicopters, divers, dogs and sonar equipment. Colby, who disappeared April 27 while canoeing near his waterfront home in southern Maryland, was found lying facedown in a marshy riverbank.

An autopsy found that Colby, 76, had suffered from hardening of the arteries, Chief Medical Examiner John Smialek said in a statement. The death was ruled accidental, rather than from natural causes, because even though there was evidence Colby was ill before falling out of the canoe, in the final analysis it was the drowning and hypothermia that killed him, said Jeannette A. Duerr, a spokeswoman for the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Hypothermia is a dangerous drop in body temperature. No blood clots were found, although they could have dissolved during the week-long search for his body, the medical examiner said. The autopsy also showed that Colby had died a short time after eating, and that he had a blood-alcohol level of 0.07 percent due to having wine with dinner. No drugs were found in his system, the medical examiner said.

Colby capped a long career in intelligence by serving as CIA chief from 1973 to 1976 in the Nixon and Ford administrations.

A private funeral service was to be held Monday at Arlington National Cemetery where he will be buried with full military honors. A public memorial service is scheduled for Tuesday at Washington National Cathedral.

From a contemporary press report:

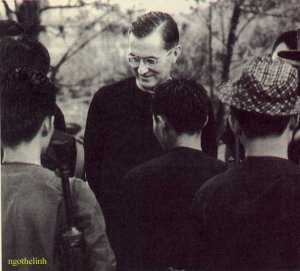

May 5, 1996 — Former CIA director William E. Colby wasn't the sort of fellow who liked to be addressed as "Mr. Colby." "Call me Bill, please," he asked in his affable way.

In his last media interview April 23, four days before he collapsed and drowned while canoeing near his southern Maryland weekend retreat, the ex-spy chief appeared more youthful and vibrant than you might imagine a 76 year-old should look like who began his long intelligence career as a commando parachuting behind Nazi lines with the Office of Strategic Services in WWII.

Nor did Colby seem beaten up by his extensive experiences in both the Vietnam War and the Cold War, two terribly different yet impossibly intertwined American conflicts.

"I've been lucky," Colby said, smiling modestly, insufficiently summing up on the streets of Washington his life and CIA career.

It was appropriate to chat with the retired spymaster over a cup of espresso at a sidewalk cafe near The White House; Colby would insist on paying, of course.

Besides his tenure as director of central intelligence in the early seventies, Colby may be best known as the head of the CIA's Far East Division during the hottest period of the war in Vietnam.

For nearly 15 years, starting in the late fifties, Colby ran the CIA's covert operations in Southeast Asia, including the notorious Phoenix Program, designed to ferret out the Communists' political infrastructure in South Vietnam.

In later congressional testimony, Colby admitted the program had assassinated over 20,000 of these suspected agents.

"I've defended [Phoenix] as a necessary element of the war," Colby said.

"The communists, curiously enough, say it was the most effective program ever used against them... The Phoenix, I always thought, was not all that effective. But if you have a secret mafia inside your population you better find out who they are, and that was what Phoenix was all about, to identify who they were. And if so, [they should] either be captured, convinced to surrender, or in a fight, shot. It was a war."

In seeming contradiction to the bloody and corrupt tactics of that assassination spree, there is evidence to support the notion that Colby wanted to help the Vietnamese people. He supported the broader Pacification Program, which encouraged and helped villagers to protect their hamlets rather than live as refugees and see their homes destroyed by Viet Cong attacks — or American bulldozers.

"We would take people out of the refugee camps and put them back in their old villages, put some protection around them, give them some guns to protect themselves, begin to rebuild the village, or the bridge, or the irrigation ditch or whatever was necessary, and they would start up their lives; really decent lives. That was the strategy [of the Pacification Program]," Colby said.

After leaving the Republic of Vietnam and the battles that ultimately consumed the small nation, Colby continued to ascend the ranks of the CIA. The well-known architect of many of the Agency's dirtiest tricks became more and more open about them.

When appointed director, he revealed so much to Congress that some of his colleagues whispered that Colby must be a KGB asset. President Gerald Ford soon dismissed him from the job after only two years, in order to appease the critics. Of the nagging conspiracy theories suggesting CIA involvement in President John F. Kennedy's assassination —

Colby was in Vietnam in November 1963 — the former director said: "Oliver Stone came to see me once to get the material released that the CIA had, and I said I believed in releasing it, maybe save the names of a couple of agents.

"Believe me, if the CIA had anything to do with the murder of our president I would havediscovered it in the early seventies and I would have revealed it — I revealed a lot of other things."

Bill Colby was the perfect product of an age where honor meant honesty, and a bone-crushing handshake meant more than just a simple greeting. It explained character. Arguably, however, Cold War super-spies such as Colby helped to perpetuate the pop culture cliches which molded entertainment icons such as James Bond and Mission Impossible in the movies and on TV, and this in turn shaped how we think of the trench-coat life.

The champagne socializing, slicked-back hair and natty dress (intentionally a little plain in the case of Colby) all were perceived attributes of the high-profile Intel-operatives of his era.

And so, to some it was no surprise that the normally low-key Colby recently consulted on a project in which he also starred — a CD-ROM adventure game called Spycraft. Colby said the game's plot was realistic and proved the need for good intelligence in the post-Cold War era.

"The premise [of the game] is, you are a CIA officer and you're told a Russian presidential candidate has just been assassinated," Colby explained.

"The President of the United States is next on the hit parade."

A realistic scenario in 1996?

American presidents have been assassinated before, Colby pointed out. "It could happen tomorrow."

For Spycraft, Colby teamed up with Major General Oleg Kalugin, the former chief of KGB foreign counter-intelligence, who now lives in Washington.

Both men portray themselves in the game, and each help the player in solving the mystery.

Greeting Kalugin at my office after the interview, Colby invited the Russian to "visit my dacha on the river. It's almost warm enough." It was from this dacha on Maryland's Wicomico River that Colby ate his last meal.

Regarding his conciliatory attitude toward a former Cold War adversary, Colby said: "We fought the British; we fought the Spanish; we fought the Germans; we fought the Japanese. Now they're our best allies.

I'd like to see that kind of relationship develop with the Russians in the years ahead."

As I sat down with Kalugin, Colby wished everyone well and left.

Moments later, I realized I had forgotten to ask him to autograph a copy of Spycraft and ran down a flight of stairs to intercept him.

I ran out onto the streets again and looked for him up and down the empty blocks.

But, true to his nature, the old spy had simply vanished into the day.

William Egan Colby

EDUCATION DEPUTY DIRECTOR

EARLIER CAREER

LATER CAREER

Colby became the subject of a different mystery in April 1996 when he disappeared while canoeing on the Potomac River. He was missing for nine days before his body was found in a tributary. An autopsy revealed that Colby, age 76, had possibly suffered a stroke or heart attack before falling into the water and drowning.

The prospects that William E. Colby was Deep Throat dim considerably in light of Woodward's assertion that he would reveal Deep Throat's identity upon his death. Colby's widow, Sally Shelton-Colby, a top official at the U.S. Agency for International Development, characterized the idea of her husband as the secret Watergate source as "preposterous." "My husband wasn't Deep Throat," she said. "Bill just didn't have it in him."

Links:

DCI John Deutch Statement on Death of William Colby A Conversation with William Colby William E. Colby Oral History Interview Ambassador William Colby, "Turning Points in the Vietnam War"

Việt Nam Cộng Hòa Muôn Năm

Xin vui lòng lưu bút tưởng niệm đến các vị Anh Hùng của QLVNCH

Please visit and sign our guestbook to honor the ARVN Heoes and to remember the thousands of civilians murdered in Hue City in 1968.

since

Memorial Day 1999

|